Step Two: Bend an Arch

First, let’s come back to the initial vision of the HoHo Hotel.

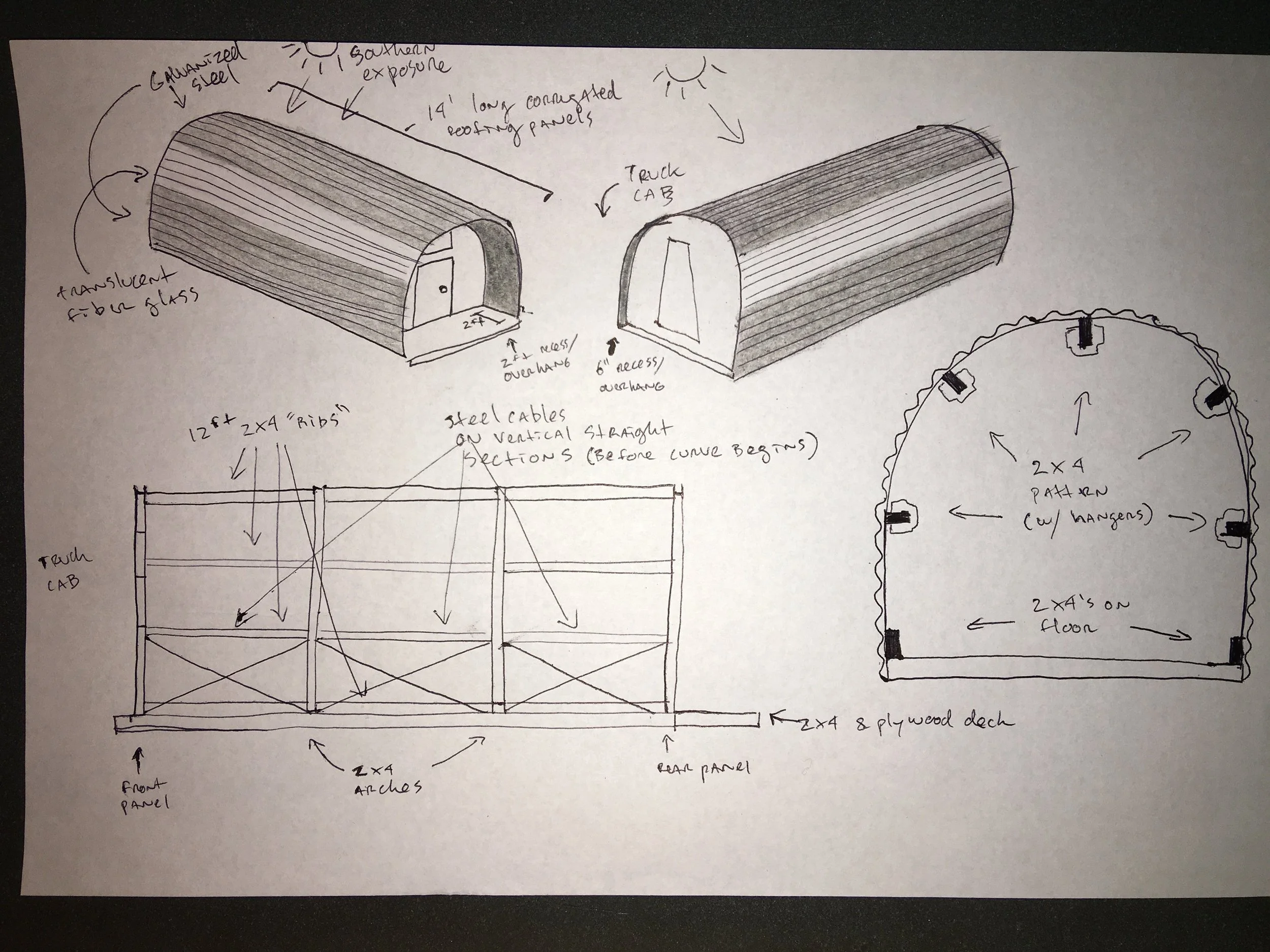

You can see that the initial vision was somewhat different. Granted it’s a napkin sketch, but I tried to capture my thinking at the time as clearly as I could. I was imagining less height to the structure for aerodynamics (option 3). I was also envisioning building a fairly rudimentary series of arches (and fewer of them). They’d be chunky, rough (relative to what I ended up producing), and constructed out of 2x6s or 2x8s. Between them would be 2x4 braces attached with hangers (an ugly but functional choice). I wasn’t too concerned about the internal aesthetics because I assumed it would all get covered up anyway.

It’s worth explaining my strategy for completion.

Some people assume that I set out to, and did, build a fully functioning mobile tiny home. This was never the plan. Oh, there’s a kitchen in there! Can I see what you did with the bathroom? No, no, I’m literally going eat at Arby’s and shit in a bucket.

The plan was always to build a watertight and windproof shell, fill it with my stuff, and go. For budgetary and timing constraints, it made the most sense to only make a “minimum viable product.” I figured that once I got to the east coast I could decide what to do with it there. Probably take it off the truck and then add insulation, maybe electricity, perhaps expand its footprint, build a deck, add nice flooring, and make some decorative touches. Ideally, this would all happen on a piece of land belonging to me, but my folks were on board with it living permanently on their land (assuming permission from their intentional community cohort). Make it simple, make it strong, make it fast. That was the plan.

But I couldn’t help myself— I needed it to be beautiful too.

Which wasn’t simple or fast. So I temporarily traded my sleep and serenity to achieve these aims. And I pointed my artist’s magic wand of beauty-making at the arch design. A friend, and former coworker, Willie Hatfield steered me toward making laminated arches, “I think you’ll really like the aesthetic.” And damn, he was right. I loved it.

There it was. Oooooo, it gave me shivers. That’s what I was going to build.

After assessing the available materials at the bargain shop I determined that I could use this one type of Bender Board (used for edging in landscaping). It was substantially narrower than I was hoping for, especially since I’d be cutting off the rounded edges. This meant that I’d build almost twice as many arches, since they’d be half as thick.

The truck bed proved to be a great bench for the project. I could screw things to it, lay stuff out, draw on it, climb on it— whatever I needed.

The length of the flatbed worked well for ripping down the bender boards, I would angle the saw and run them diagonally across the bed, maximizing the amount of support under them as they passed through the saw. I’d then reset the saw and trim the second edge. Did this (what felt like) hundreds of times, though it could have been more than 150 pieces.

That big pile of sawdust there, that was gold. I’d learned from my days at Aprovecho, exclusively using a composting toilet for a full year, that the quantity and quality of your sawdust mattered a lot. See, the sawdust gets sprinkled onto your poop, it absorbs the moisture and dries it out, and it does a remarkable job of neutralizing the odor. What you want are the small fibrous pieces (not the pure powder) and you want A LOT of it. Nothing worse than running out of sawdust. Not even toilet paper, because the sawdust can be your toilet paper, but not the other way around. The stuff pictured above was the exact kind I’d need for my own road trip composter, and I had it in spades. Permaculture baby, stack those functions.

I snapped a center line, and then used a 2x4 as a compass to draw out a semi-circular form on the bed of the truck for the arches. Out of excitement I slapped down some blocks and did a quick dry fit of the arch shape just for the pleasure of seeing it. Little moments like these were important to egg me on.

For the outside of the house, the side with the door, which would be facing behind the truck, I wanted to make that arch a little differently. I couldn’t explain why logically, just something about wanting a slightly different aesthetic for the outer arch. I envisioned it being split into three pieces and bolted together with big thick bolts. I imagined the wood of the legs being a different hue than the arch, likely red for the legs and blonde for the arch. I would custom notch them together, a bit like in traditional timber framing, except with beefy metal bolts painted matte black.

This particular vision made that upper arch the perfect one for a trial run. It was small, therefore, requiring less material (i.e. less to replace if I fucked it up) and would be easier to maneuver and manipulate.

I watched a few videos on laminated arch building (god bless the endless repository of arcane knowledge that is YouTube) and started in like I saw one guy do, with a giant ratchet strap.

I built some blocking and screw it to the frame using the reference of the large semi-circle I’d drawn earlier. I put down a sheet of thin plastic dropcloth because I didn’t want to accidentally glue my arches to the flatbed. Oh, that’s what lamination is, in case you didn’t know, it’s gluing thin layers of wood together. By putting a whole mess of glue between the layers you can manipulate them into a shape and then fix them in place. But the truck bed was not the place I wanted them fixed, so I stocked up on plastic sheets large enough to cover the whole bed with a single piece.

Before committing to the mess of glue, I wanted to do a dry run, see if there were any kinks to work out before committing. Because once you lay that first bead of glue, the clock is ticking and you have to hustle. So, I stacked my boards, pinched them in place with some clamps and then strapped them into the form I’d built.

The dry run showed some issues with the form and the process. For instance, the boards pulled apart as they were being tightened down.

Also, the strap was really struggling to make the 90 degree bend down at the bottom, to the extent that when I removed one of the clamps, the whole thing sprung open.

It was clear that I’d need to change the strategy for the glue up. First off, I’d need to ditch the strap, it just wasn’t working like I saw in the video online (the person was also doing a much smaller job). Instead, I’d use a trick I’d learned from an old builder, Butch, when I was constructing homes at the Quaker eco-village in upstate NY. The trick is to, well, you’ll see in later photos.

The other issue, which I didn’t foresee, was that the dry run was bad for the real thing. Namely that it curved the boards, and that curling was bad for business when it was GO time.

The problem the curvature created was that the boards didn’t sit flat during the glue application. The boards sitting flat on each other is important because it, as I was about to find out, keeps the glue from drying out too quickly.

The curvature/exposure issue was exacerbated by the fact that I was stingy with the glue. I didn’t want to use more than I needed, my goal was to minimize the sanding I’d have to do and I figured that too much glue oozing all over the place would be wasteful and make more work. Also, it never occurred to me to pre-soak the wood in water, which meant that it was bone dry to begin with.

Because of the light application, the curved exposure letting air flow, and the lack of pre-soaking each initial pass was dry by the time I came back to do the next one. I didn’t notice at first, but when I did, I started to lose it. Cursing out loud, I began rushing the passes, not thinking to just start over, or to use copious amounts of glue. In a haste I sandwiched it all together and carried it to the truck bed.

In between the dry fit and this first live test I had made an adjustment in strategy. The dry fit had shown that the strap-bending-method was insufficient, it just couldn’t create enough force to make the full bend (the right angles and ratchet placement were to blame). So, I instead turned to a trick I’d learned from a gravely-voiced, salt of the earth, roofer named Butch. The method is to take a rectangular piece of dimensional lumber, cut a diagonal through the middle, then screw one of the pieces to your substrate, wedge the other one between it and the thing you want to clamp/move/bend, and then whack it with a hammer. Repeatedly.

It’s a little hard to see in the image below, but those blocks along the outer edges are the ones I’m describing. I also employed a healthy dose of clamps. With both the clamps and the blocks I thought a protective layer of wood was needed, for the clamps primarily to avoid putting ugly marks on the visible inner side of the arch, and for the blocks (outer side, not visible) it was exclusively to avoid accidentally gluing to them.

The bending process kept separating the boards from each other, laterally. Every so often I’d have to run down to the ends and whack it with a hammer to get it to move back into place. One of the perils of the quickly drying glue was that it wasn’t (as I’d later discover) enough to actually hold the thing together, but it was enough to keep the boards from being able to move back into place after they’d slid apart. Oi.

The photos really don’t capture the panic of this process. It was fairly stressful and I was flustered, to say the least. And during this most inopportune time, an oblivious little old lady wandered up and started peppering me with questions. How she saw my furious activity as something to casually interrupt I will never understand. “Oh, what’s that? What are you making?” and even in my sharp focus and searing anxiousness, I politely responded, “I’m making an arch.” That wasn’t sufficient, she needed more information and picked this exact fucking worst time to interrogate my efforts. “What’s the arch for?” and, again, though with a distinctly annoyed tone, I made the effort to respond “for a tiny home.” “Oh, a tiny home! I love tin..” I cut her off “I’m sorry, this is a very stressful and time-sensitive operation and I don’t have the capacity to talk right now.” There was a pause, “Well, excuuuuse me, I was just showing interest in your work.” Oooo… lord help me, I could have smacked her. Instead, I just ignored her until she walked off in a huff.

I waited 24 hours to give the glue time to fully dry. Coming back a day later, I took the arch out of the jig, and I could see right away that it would need some serious re-work. I mean, I already knew that, but now I could see the full extent of it. The form didn’t hold at the bottoms where I attempted to make a straight run, plus the boards were separating aggressively. I put it up on some saw horses, started removing the clamps, and then POP, pop pop, crack.

Fuck.

The weakness of the glue, combined with poor joint placement, resulted in structural failure. But I didn’t want to scrap the arch, in part because that’s not my style, but in larger part because they only had so much of this particular off cut at the bargain bin. The way the bargain outlet worked is that they get whatever damaged, improperly milled, or otherwise “unsellable” lumber the mills reject, and it’s a total gamble, never the same thing twice. Basing my project off their wood supply was risky, but it was what I could afford. So, even having purchased a buffer beyond my cutlist, it followed that I would aim for zero waste, even if it meant annoying (and ugly) fixes.

Going back at it, I dribbled lots of glue (making no effort to conserve this time) into the gaps that had formed, and painting a thick coat onto the separated boards. I then reclamped it back into shape, and added an extra spacer at the bottom to get a tighter curve and desired following section of straight run. Here the straps worked beautifully for cinching the arch into the desired shape. I was concerned about inadvertently gluing my outer barrier board to the arch (given the liberal application of glue) and pre-emptively wrapped it in spent plastic sheeting. I figured that scraping or sanding off a thin film of plastic would be easier that removing a glued board.

The results were, at first glance, pretty good. Or, at least, an improvement. I mean, the thing didn’t pop apart when I took the clamps off. But I still didn’t trust it entirely. It occurred to me, for better or worse, that running some dowels through it while I had it under tension would help to retain its shape, give it some extra rigidity and minimize any further splitting once I pulled the straps off.

This method kind of worked. I don’t know how much it kept it from splitting or widening further, but it also didn’t exactly lock it in place the way I’d hoped it would. There were still creaks and crackles when I took the straps off and the straight sections got absorbed into the curve. The distance I needed to span was close enough that I thought I could flex it back into place when the time came. Not ideal, but also not a total fail.

4/10 for my first attempt.