Step One: Make a Flatbed

I don’t remember the exact date that I was handed the keys to my truck, but it was sometime in the spring of 2020. The very first thing I wanted to do with it was DRIVE. Drive for hours. Drive into the woods. So I did. And I was in love.

Something interesting that surprised me during my lengthy, 6ish hours, initial test drive was how conspicuously others reacted to me. This thing is massive. And tall. And also very weird looking (then and now, but more so then). Firstly, I could see everything. Wide-angle mirrors, huge windows, and my vantage point has to be around 7 feet up. Plus, because there was nothing on the back, no truck bed, no box, just a low and open frame, I could look behind me and see the ground under my truck. All of this amounted to the greatest visibility I’ve ever experienced in a vehicle. It might not sound all that interesting or noteworthy, but it was incredible, and it made driving both more safe and more fun. But the real fun came in seeing people’s reactions. The unspoken law of the road is that big wins. Without trying, not even driving aggressively, people consistently got out of my way, gave me space, let me merge, and generally deferred to me. Having previously only driven small cars, like my trusty Justy, this was entirely new and unanticipated. It’s one thing to describe it, it’s another thing to experience it. I won’t pretend to be neutral here: I loved the “respect” I was now given on the road (especially compared to being a cyclist in traffic) and how powerful it felt.

That “respect” was also reflected in the faces of the dudes (and occasional ladies) who’d roll up alongside me. It seemed like guys were speeding up to ride in parallel and flash me approving hand waves, head nods, or wide-eyed gazes of envy and disbelief. Again, I’m driving this thing without anything on the back, not even a flatbed. Just a naked ass, diesel, dually.* I swear they were popping boners. Driving it felt kind of like having a massive boner.

*Dually means dual-axle, i.e. 4 rear wheels for extra weight carrying capacity

It was the weirdness of the truck that made it all work. Its status as a boxless box truck made it unsellable by the dealer, and therefore an amazing deal— you have to understand that Sprinters, in large part due to their #vanlife influencer status, command a hefty price, even in resale. Used Sprinters in terrible shape go for several thousand above bluebook value. This one was in excellent mechanical shape, great physical condition, well-maintained as part of a fleet, and selling for several thousand below bluebook. That’s unheard of. And it was entirely because, in their words, “nobody knows what to do with it.” I didn’t exactly know what to do it either, but the openness of it, the potential of it… it wasn’t a barrier at all, it was a thrilling opportunity: I could build anything I wanted.

I drove away from the dealership, title in hand, literally shouting “I got I truck. I GOT I TRUCK.” A colloquialism in my family is “I got I ______ (fill in the blank)” for anything we’re childishly excited about, the phrasing of which is credited to my toddler self for successfully sitting still in pre-school and receiving the reward of a sticker. I also threw in a “WHO’S TRUCK? MY TRUCK.” Which would be unrecognizable to anyone else, even in my family, but was a retort to the emasculating “life advice” that my father liked to periodically offer up that I should “find a woman with a truck.” A modern twist on the equally insulting and unwelcome “you should find a man with a good job” that many a capable woman has had to slough off ad infinitum. No thanks, I can take care of myself.

So now, the proud owner of a very large, very odd truck, what was I to do? Just what would I build, and how would I use it?

A flatbed to start. Something simple. Something I could strap stuff down to, which would also, hopefully give a little protection to the chassis.

Covid had wrecked plans I had to visit friends in California, but I still had the time off from work, so I used it to construct the flatbed instead. I went and stayed with some Aprovecho friends on their off-grid homestead in Cottage Grove (Heather and Brad and their adorable kiddo Pixie). I don’t think I have any remaining photos from that initial build or visit with Brad and Heather. But here are some photos from a recent visit that give you a sense of their place. It’s preceisely the kind of verdant-strawbale building-hippie-magic that I associate with Oregon. Replete with a precious nappy-headed feral Indigo. Lol.

Brad and Heather were among the very first people that I became friends with in Oregon. They are still very near and dear to my heart all these years later. It was wonderful to be able to spend a week at their place building out my truck and being silly with their adorable offspring. I’m so bummed I can’t find photos from that first build in 2020! Ah, so it goes. (Oh, random aside, Brad and Heather used to live in NJ and where they worked on a farm with my cousin Robin long before they ever met me in Oregon… what a small, small world).

The build was simple. Lay 2x4s across the frame, doubling them up over every spot with an attachment point, bolt it down, and sheathe it in 1/2” ply. Brad was nice enough to let me use all his tools since I didn’t have any real power tools at the time. It all took a lot longer than expected, but I got it done with plenty of time left over to visit, nap, and go on woodland adventures with Pixie. Somehow, inexplicably, I subsisted on Poptarts and Coke the entire visit. Weird choice.

Having the truck was useful for moving house, though, not quite ideal. Most of the trips looked something like this, a small, centered pile of things strategic layered to be strapped down with one really big ratchet strap:

I had envisioned hiring myself out as a mover of things, doing it as a side hustle. In the pictured arrangement, this would be laughable. So I’d need a real flatbed, made of metal, with places to hook to, spots to drop in fences, and (my favorite idea) a hydraulic lift! But the upfront costs for getting a proper flatbed (even one without a hydraulic lift) were prohibitively expensive. I had just spent ALL of my (and a lot of other people’s) money buying the thing, I just didn’t have the cash on hand to immediately upgrade it. Therein lies the catch-22 and capitalist rationalization for lending: I needed the flatbed to earn the money to buy the flatbed…. leaving a loan as the only real answer. However, I wasn’t confident enough in my idea to go take out a loan. Also, I fucking hate loans and want as little debt as possible. I owned this vehicle outright. It’s debt-free status was a huge win, and not one I particularly wanted to give up.

So what then? What would I do?

I would think about it. And wait.

And in the meantime, I’d drive into the wilderness on occasion and scream from a cliff top while feeling all of the despair associated with lockdown, isolation, and a collective crisis.

Almost a full year went by since building the flatbed. It got rained on a lot (because Oregon) and looked increasingly sad. The prospects for the vehicle, in general, looked increasingly sad. I had resigned myself to selling it. I’d “lose” money, but since it (mostly) wasn’t my money to begin with, I’d actually be making money. But that wasn’t comforting in the slightest. I wanted to do something awesome with it. I just didn’t know what.

Until I did.

Fast forward: phone call with sister, decision to move, put in for a transfer to Philly, get it, look into u-haul costs, and BAM there it is. Now I know what to do. I’m going to keep my weird and wonderful truck, I’m going to make a tiny home on the back, and I’m going to traverse the Reverse Oregon Trail.

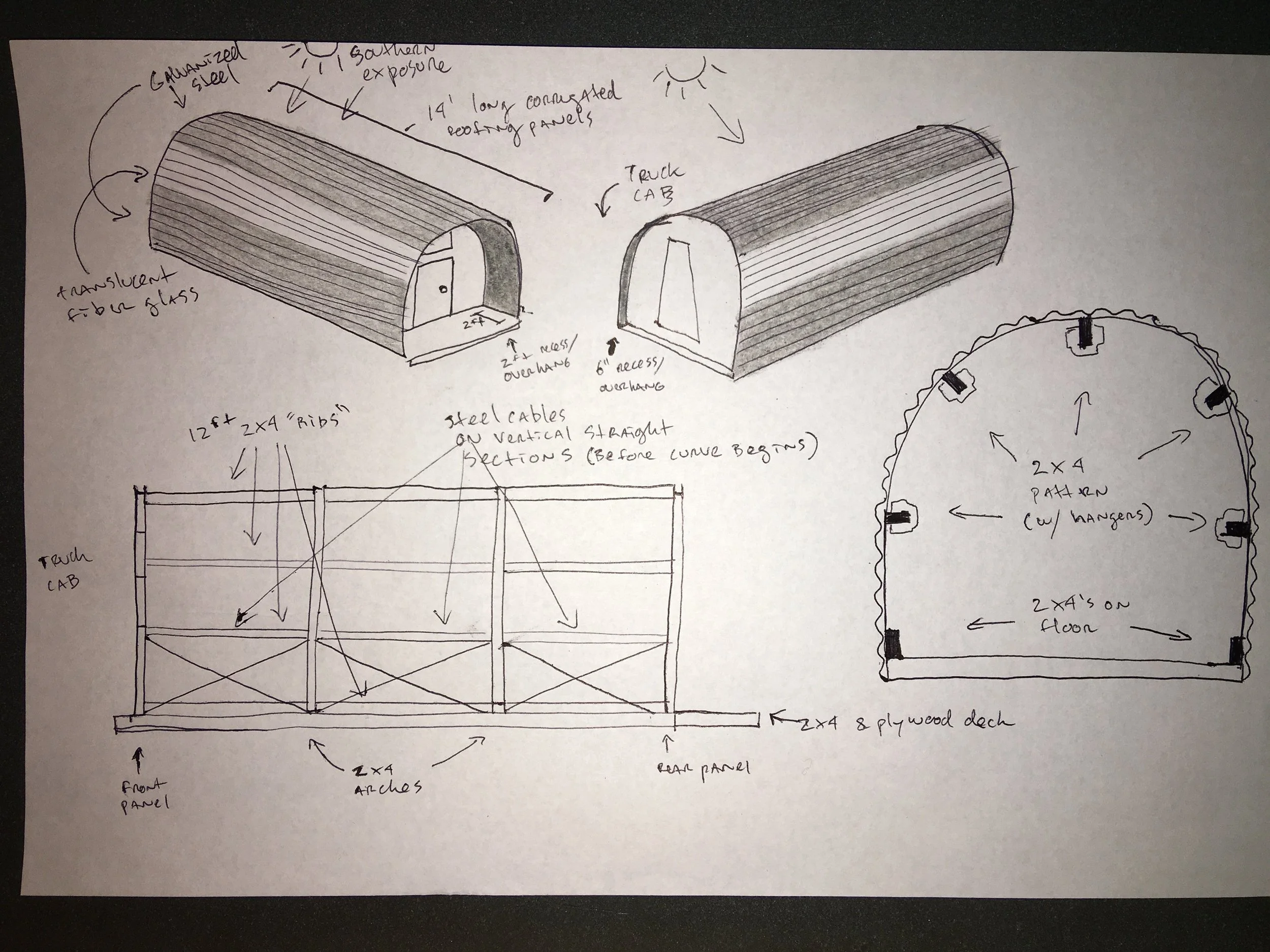

A Conestoga Wagon was the natural choice.

Quick side story- so while I was gearing up to make the move, I was directing my attention toward the most tantalizing opportunities in Philadelphia, à la Zillow & Tinder. I spent a whooooole lot of time looking at houses, and a modest amount of time looking for dates. One such dating prospect, not entirely impressed with the drawings for what I hadn’t yet built, said it looked like a HoHo. You know, the Little Debbie’s snack cake. When I recounted this to a dear friend and fellow former Oregonian, Eleva, she guffawed and dubbed my wagon the HoHo Hotel. Which is fucking brilliant, and the closest thing to an official name that my vehicle has. But I’m reluctant to make it official, because… still stings a little, Tinder lady.

When building a house, even a HoHo Hotel, the foundation comes first. I’d need to revamp the platform asap. I wasn’t sure what I was going to find once I’d pulled it apart. Honestly, I was expecting the rain damage to be significant and possibly total. I thought the plywood would be so molded and warped that it would be unusable. Thankfully that was wrong, especially given the surge in prices in lumber that came along with the pandemic (apparently I wasn’t the only one channeling my energy into building stuff). Once I actually started ripping the thing apart, I was very surprised at how well it had faired. I mean, there was a little mold, but it was on the surface. Nothing was rotting. That was key. Surface mold could be sanded off. And it was.

Just to be on the safe side, I gave all the wood a fine misting of bleach infused mineral water. Nothing like chlorine to kill shit.

While I was at it, I flipped all the external 2x4s around, so the unweathered sides were now facing out. That and flipping and sanding the plywood went a long way towards freshening everything up.

The patterning here is, admittedly, a little strange. But there’s a logic to it.

The cross-pieces at the very ends are what complete the rectangular shape and retain it’s outer boundaries. But that’s not where the bolt holes are on the chassis. And that’s a key point. To properly secure this thing to the vehicle I’d need the bolts to go through the beams, not simply through the plywood sheathing (obvious to a builder, but perhaps not to you, general public). So (almost) everywhere you see those doubled-up cross pieces, that’s where the bolt holes are in the frame. I doubled up the 2x4s to increase their strength, they are strongest and can bear the most weight standing up on end, and when you sandwich two together you’re getting more strength, also more surface area to bolt through (the bolts, which you’ll see later, are beefy and drilling through a single 2x4 would have been… questionable).

Now, some of those doubled up pieces are just to undergird the transition from one sheet of ply to another. I didn’t want to have a seam between two sheets sitting atop a single 2x4. That’s a lot of vulnerability for the sheet under pressure (from cargo or me walking around) to have on a 3/4” lip. So each end of the sheets is supported with a full 1.75” 2x4 (yes, you read that right, 2x4s aren’t actually 2“x4” anymore, they’re 1.75”x3.5”) (nominal wood sizing is stupid, much like a lot about American standards). All of the single pieces you see intermixed are there to bridge the distances between the doubled beams. Not super necessary, mostly for feel. The bounciness of those big gaps, I didn’t like walking on it. Too mushy.

While I had the plywood drying in the sun from its bleach-treatment, I stopped by the local discount-lumber joint in town. It helped for this project that I was living in one of the most lumber-rich parts of the country. Even with the spike in lumber prices (a sign of things to come) I was able to get rejected lumber dirt cheap.

Having the sheathing off actually made it a lot easier to strap stuff down. All those small pieces there, that’s the red hued Doug fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) that I’d later laminate into arches.

I wanted the arches to appear almost as if a single, steam-bent, piece of lumber. Like out of the wooden sailing ships of yore (oooo, that would be a fun next project). So, I had to go about ripping them down because they came milled with rounded edges. Annoying for me. Useful for someone, apparently. The rounded edges, I mean.

While I got started on that, a friend and former coworker, Justin, got started on sanding off the now bleached mold spots. It’s funny the extent to which working on something attracts others. Like, I didn’t ask for assistance, but people kept offering it. Which was a mixed bag. I got lots of help, but not all help is equal. Some help —and this is challenging when it’s friends who are generously volunteering— isn’t actually all that helpful. Sometimes people come in and require so much hand-holding that it’s a net loss of time. This was very minorly the case with Justin, he was, to his credit very humble about his ability to assist and fully willing to take whatever small task I could hand off. So sanding it was.

Bless his heart, sanding with me into the night. Justin, you mensch.

That is an honest-to-god bike light we’re using as a work light, albeit a very powerful one. What it’s attached to… is a secret.

The big blocky thing you see down at the end of the flatbed is a table saw borrowed from the Toolbox Project in Eugene. Brief plug— my friend Anya started the TBP and it is an incredible resource for any of y’all reading this in the Eugene/Springfield area, you can go borrow (for free or very cheap) the kinds of tools that you would otherwise have to invest hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars in. Tool lending libraries (many traditional local libraries are actually now adopting this lending service as well) are invaluable for anyone who, like me, has a one-off project in mind. Makerspaces are another really good resource, though they’re more ideal for ongoing projects that require large-scale equipment (waterjets, lathes, etc.).

Despite my best efforts to get everything square, true, flat, and flush I didn’t quite nail it on the platform. Specifically, its square. So, I snapped some lines and trimmed it square. Why does that matter? It matters because when you build something, everything compounds. So, if your foundation isn’t level, your house isn’t level. If it isn’t square, your house isn’t square. That’s why the foundation metaphor gets tossed around so often, because it really does matter to get that part right. And if you don’t, you then suffer having to correct for this initial incorrectness for the rest of your building project. This is why finish carpenters generally hate framing carpenters, because framing carpenters operate with (relatively) huge tolerances that the finish carpenters then have to go back and continually correct, fudge, and fix.

In this particular instance, the most time/energy efficient thing for me to do was trim the edges square. Ripping it all down and starting over would have been a massive time sink, and honestly, probably not made much of a difference in the end result. This was a way that I could keep things lined up for successive processes without wasting epic amounts of time (remember, the doomsday clock of joblessness was ticking).

The results were pleasing. Seeing the flatbed revitalized was just the shot of confidence I needed to embark on the next step: the arches.